Janice Bright describes how minimally invasive treatment for advanced COPD improved her quality of life.

10:30 AM

Author |

Like most grandmothers, Janice Bright would do anything for her grandchildren. When her advanced lung disease began to get in the way of taking care of them, she knew she had to do something. Bright, who is 70 years old, was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 15 years ago, but noticed it getting worse over the past four years, leaving her increasingly unable to do the things she loves.

Things like attend her granddaughters' softball and football games.

"I could go but I'd have to bring my oxygen and leave early. Being around people made me sick all the time," she explains. Even at home, she was limited in what she could do. "I couldn't do housework, laundry; I couldn't do anything."

Some mornings, she says, she'd wake up unable to take a breath deep enough to even speak. Instead, she'd ring a bell, and her husband would come running to see what she needed.

COPD is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States, affecting 16 million people. Its symptoms, including chronic cough, fatigue, and shortness of breath, tend to worsen over time. While there is no cure for COPD, there are various drugs and therapies available to treat these symptoms.

And while treatments like pulmonary rehabilitation, medications such as bronchodilators and corticosteroids, and lung volume reduction surgery help many people living with COPD, a new option called the Zephyr Valve, which was FDA approved in 2018, is offering hope for patients like Bright who have advanced disease. Michigan Medicine is one of only a few hospitals in Michigan to offer this treatment option.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

"With COPD, the lungs become bigger, or hyperinflated," explained Dr. Jose De Cardenas, clinical assistant professor of internal medicine at U-M Medical School in a recent video on COPD. Many of Bright's symptoms, including her shortness of breath and uncomfortable gastrointestinal symptoms, are the result of her overinflated lungs pressing down on her diaphragm.

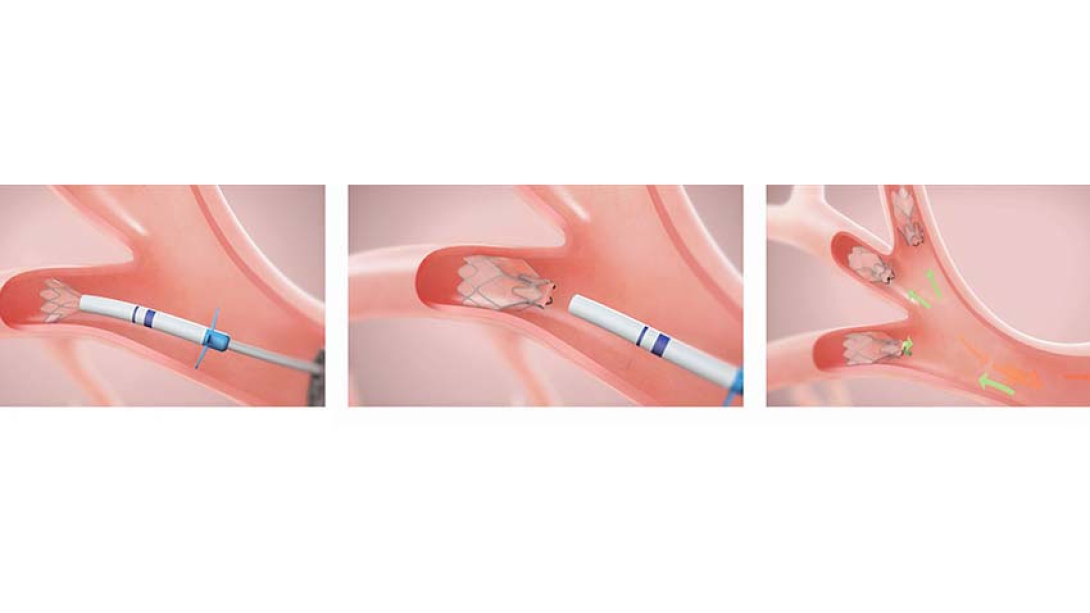

"What we're trying to do with the valves, which are extremely small, is to put them inside the 'bad' diseased part of the lung, in order to block the air from going in," De Cardenas explains. As a result, the non-diseased portion of the lung can expand and relieve the pressure on the diaphragm, allowing patients to breathe better.

"The Zephyr Valve is best suited for patients with advanced COPD who are breathless at rest or with activity despite optimal medical management and who have significant hyperinflation and air trapping due to destruction of lung tissue," explains Dr. Wassim Labaki, clinical lecturer and research fellow in internal medicine.

Bright's pulmonologist recognized that her options for further medical treatment were running out and suggested she look into the Zephyr Valve placement. She insisted on going to U-M for care.

"We review all potential cases at our twice monthly multidisciplinary Lung Volume Reduction Conference, involving pulmonologists, interventional pulmonologists, thoracic radiologists and thoracic surgeons, to discuss best treatment options for each individual patient," says Labaki.

Bright was the perfect candidate. After some tests and X-rays, she met with De Cardenas, whom she affectionately calls Dr. Pepe. "Dr. Pepe described how they put them in and how the air moves around them," recalls Bright. "He said, 'I'm not guaranteeing you'll be completely off oxygen but I am guaranteeing you'll have a better quality of life'."

That was all Bright needed to hear.

During the procedure, the stents are placed into the patients' airways leading to the most diseased parts of the lungs using a bronchoscope, closing them off. Afterwards, Bright recalls being astounded the first time she took a deep breath. "I said to the nurse, 'oh my god, what is happening?' She laughed and said, 'you're breathing.'"

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device or subscribe for updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

Recovery, Bright explains, has been about regaining her strength, putting faith in the valve and gradually reducing her use of supplemental oxygen.

"I use the oxygen at night and when I work out on a treadmill," says Bright. "I'm tapering things down to see if I can go on the treadmill without it, just to test myself."

Bright says her life has been completely turned around after the valve placement. She's able to attend her granddaughters' games again and even travel to California to help her sister.

"My husband says you are 100% better. I'm back to doing family dinners. Do I get tired? Yes, because I still have COPD," she says. "But this is the best thing I've done in my life."

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!