Early role in “iron lung” intensive care, advanced rehabilitation, and vaccine testing

Author |

Ask someone in their 70s or older, and they’ll probably remember the fear that gripped the United States in the summers of their childhood, as outbreaks of a deadly virus cropped up across the country.

Their parents may have kept them home, to protect them from getting infected at public swimming pools, movie theaters, birthday parties, camps or playgrounds.

The reason? Polio, a virus that attacked the nerves of thousands of children, teens and adults each year. Over the first half of the 20th century, it caused permanent disability in hundreds of thousands of them, and snuffed out the lives of thousands of people each year by paralyzing the muscles crucial for breathing.

Major polio outbreaks started appearing in the U.S. around the turn of the 20th century, and one of them in the 1920s left future president Franklin D. Roosevelt unable to stand on his own. By the end of World War II, full-scale epidemics happened almost yearly. Tens of thousands of survivors are still alive, but many face lasting effects called post-polio syndrome.

Except for them, polio is now part of medical history in this country. No one has caught polio in the community in the U.S. since 1979, thanks to near-universal vaccination.

Ironically, the children who received that first polio vaccine, and got their summers back, are now the older adults who face the highest risk from COVID-19. A vaccine against the novel coronavirus may be a year or more away from widespread use. So once again, they’re sheltering at home to avoid a virus.

The University of Michigan played a special role in the fight against polio for many decades, from the treatment of its effects to the massive clinical trial that led to the first approved vaccine.

Here are some highlights from that history, as part of Michigan Medicine’s 150th Anniversary celebration of the institution’s medical heritage:

1915

U-M surgeon Charles Washburne, M.D., reported on poliomyelitis in the university’s medical journal. He wrote that even though Michigan hadn’t had outbreaks of the size seen in other states, half of the patients with ‘deformities’ referred for care at U-M’s hospital were because of the disease, also known as infantile paralysis.

Those patients came to U-M thanks to a state law passed in 1913, which allowed for children of needy parents to be sent to U-M’s hospital for treatment of any sickness at state expense. Washburne reported on successes in treating the lingering effects through surgery, massage and exercise. He noted that scientists elsewhere had made progress in isolating the cause of the disease and understanding how it was transmitted, and expressed hope for a vaccine “in the near future.”

He also called on states and Congress to pay as much attention to preventing contagious diseases in humans as they did to infections that killed livestock.

Though cities and counties had tried to prevent the growth of outbreaks, he wrote, “The stamping out of a disease is a long process, requiring time, money and authority over large areas. The state of Michigan must know by this time the treacherous nature of this disease, that it robs the state of human wealth, that its very magnitude requires the full state and national power to make its suppression a success.”

1928

James L. Wilson, M.D., the future chair of pediatrics at U-M, was a young pediatrics resident at Boston Children’s Hospital. A team from Harvard University’s nearby School of Public Health had been developing a tank-like device designed to take over for the failing muscles that kept polio patients breathing. Equipped with a continuous power supply and accurate gauges to keep tabs on the negative pressure inside the tank and the breathing of the patient, it was ready for its first test when an 8-year-old girl was admitted to the hospital. The team wheeled the “tank respirator” over to the hospital, and the girl survived nearly five days before dying of a second infection. Wilson’s mentors published the result in the Journal of the American Medical Association in May 1929, and he worked for years to improve and document the use of the experimental life-support technology.

A quote from his 1932 paper on lung failure in polio patients echoes down to the time of COVID-19: “Of all the experiences that the physician must undergo, none can be more distressing than to watch respiratory paralysis in a child ill with poliomyelitis — to watch him as he becomes more and more dyspneic, using with increasing vigor every available accessory muscle of neck, shoulder and chin, silent wasting no breath for speech, wide-eyed and frightened, conscious almost to the last breath.”

In 1941, just as Wilson’s Harvard mentor Charles McKhann joined the faculty of the University of Michigan, Wilson reported the results from 500 patients treated in what became known as the “iron lung”. Eighty percent of them, he wrote, regained the ability to breathe on their own in a few weeks. Wilson became chair of pediatrics at U-M in 1944, a position he held until 1967.

1936

With dozens of young polio patients in the care of U-M teams, a new physical therapy area, complete with hot tubs and a swimming pool, is opened in the lower level of the main University Hospital to expand the options for helping patients regain the use of their limbs.

Donations from the community, raised through the “President’s Ball” held annually since 1934 on Roosevelt’s birthday, helped support care and recreation for patients. The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, launched in 1938 to unify the national fundraising effort, soon became known as the March of Dimes, and community members from Girl Scouts to Kiwanis Club members worked to collect funds to help the U-M hospital and the national campaign. March of Dimes funding supported many research and education efforts around the country.

1941

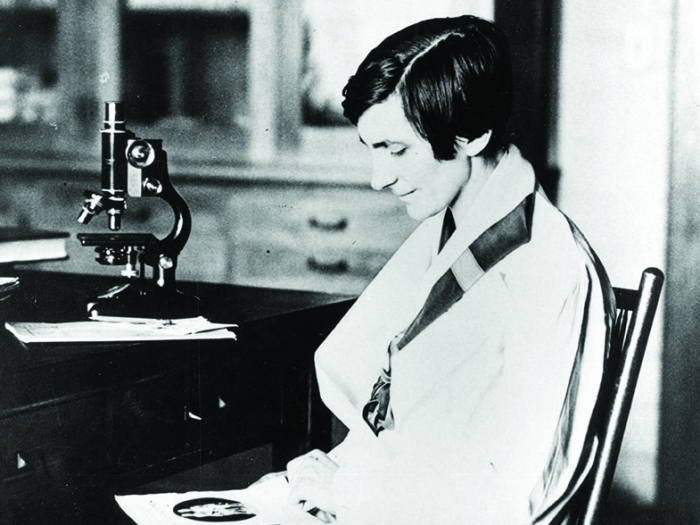

The brand-new U-M School of Public Health, recently launched as an academic unit in its own right rather than a branch of the medical and graduate schools, receives a grant from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis to study the polio virus. Thomas Francis, Jr., Ph.D., the chair of the Epidemiology department, led the work. He also worked on an influenza vaccine with a team that included a young scientist named Jonas Salk. Having learned about vaccine development during his time at U-M, Salk led the development of a polio vaccine at the University of Pittsburgh.

1951

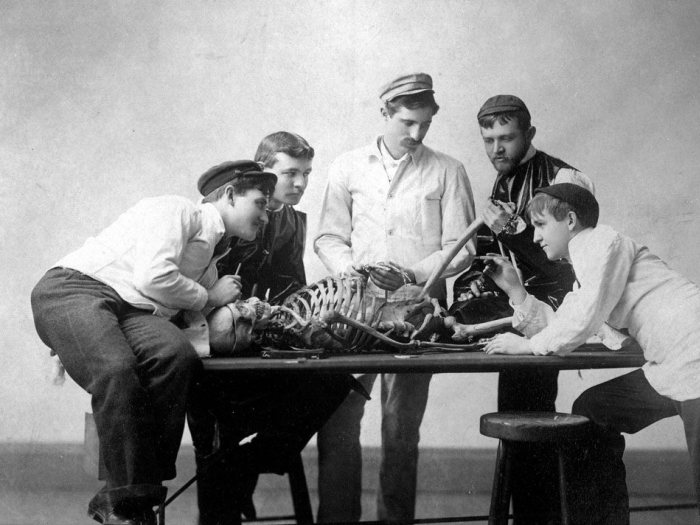

As severe outbreaks of polio nationwide left more and more young people needing “iron lungs” and other advanced care, U-M opened the nation’s third Poliomyelitis Respirator Center(link is external). Funded by the March of Dimes, and overseen by David G. Dickinson, M.D. it includes eight beds in University Hospital. A wide array of devices, and the trained staff needed to tend to the patients and equipment, helped give rise to the concept of intensive care for critically ill patients. That model, where special expertise and advanced life-support technology combine, is still in effect in modern ICUs. Read more in Medicine at Michigan magazine.

1954

Francis is appointed to lead the Poliomyelitis Vaccine Evaluation Center, and conduct a national clinical trial of the vaccine developed by his former mentee Salk. Funded by the “a million dollars’ worth of dimes” donated to the March of Dimes, it enrolled nearly 1.8 million children between the ages of six and nine – those born in the immediate post-World War II years. Some children were selected at random to receive a placebo, and the researchers were kept from knowing the results until the trial had ended and the data were analyzed. As Francis declared from the stage of the Rackham Amphitheater on April 12, 1955, the vaccine proved “up to 80-90 percent effective in preventing paralytic polio.” The news soon spread around the world.

A few weeks later, the first doses of the vaccine arrived in Ann Arbor, and schoolchildren were among the first outside the clinical trial to receive the newly approved inoculation.

Within a few years, polio was all but eradicated in the United States.

1983

The lasting effects of polioon those who had caught it before the vaccine were becoming more and more apparent, as they entered middle age. U-M physical medicine and rehabilitation experts, led by Frederick M. Maynard, M.D., launched a Post-Polio Clinic that continues today, to help patients with muscle and joint symptoms erupting decades after their initial experience with the infection.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine