A new study finds nearly 12 percent of men with advanced disease have a genetic mutation. As a result, the authors say every patient should be screened.

7:00 AM

Author |

Testing men with metastatic prostate cancer for inherited genetic mutations could help guide treatment choices and alert family members to their potential cancer risk.

SEE ALSO: Quality of Life Meets Cure for Prostate Cancer Treatment

A new study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that inherited genetic mutations were much more common in men with metastatic prostate cancer than in men with early stage prostate cancer.

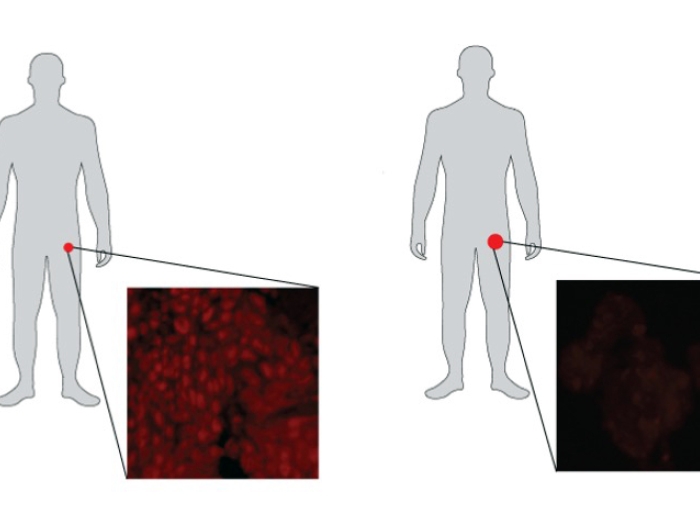

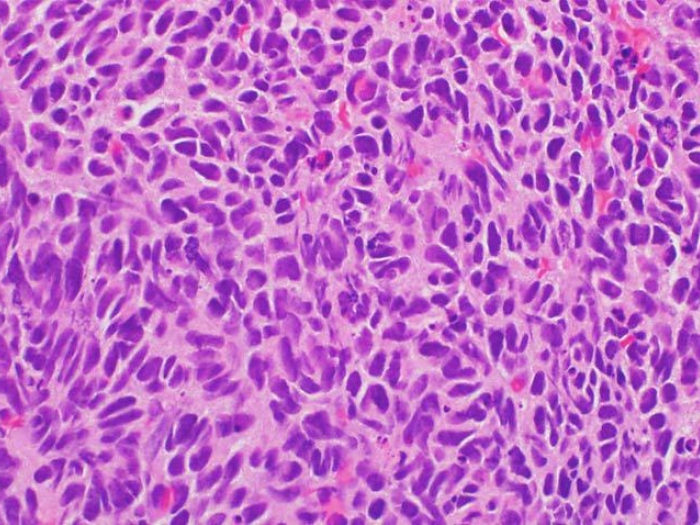

Researchers performed genetic sequencing on 692 metastatic prostate cancer samples to identify mutations that disrupt the function of genes involved in repairing DNA damage. They found 11.8 percent of men with metastatic disease had a DNA-repair gene mutation. Testing among men with early stage prostate cancer found only 4.6 percent had genetic mutations. Among men without a cancer diagnosis, it was 2.7 percent.

The most common mutation was BRCA2, which is also known to play a role in breast and ovarian cancer. Those with mutations were not more likely to have a family history of prostate cancer. But 71 percent of the men with DNA-repair mutations had a relative with cancer other than prostate, including breast, ovarian, leukemia, lymphoma, pancreatic or other gastrointestinal cancers.

The findings have two important implications, the authors say.

First, they could help guide treatment choices. Previous studies have shown metastatic prostate cancer with DNA-repair gene mutations have responded to a class of drugs known as PARP inhibitors and to platinum-based chemotherapy.

Second, identifying these mutations could trigger family members to seek genetic testing and potentially discover if they are at high risk of cancer.

Arul Chinnaiyan, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Michigan Center for Translational Pathology, is one of the study's authors and the principal investigator on the Stand Up to Cancer/Prostate Cancer Foundation Dream Team that led this study. He discussed the findings below.

What motivated this study?

Chinnaiyan: We published a paper in Cell in 2015 based on the first dataset used here. In that paper, we found 14 percent of patients had a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2, and that 8 percent of patients had some kind of inherited genetic alteration. This study advances on those findings with a much larger sample size.

Do these findings suggest that every man with metastatic prostate cancer should have genetic testing?

Chinnaiyan: Yes, we think so. The prevalence is high at 11.8 percent, especially compared to the general population. You wouldn't screen patients with clinically localized disease, but for metastatic prostate cancer, it makes sense that they would be screened.

If a patient has the germline alteration, it suggests his family members should get tested to assess their cancer risk. It impacts not only the individual, but also his family. Beyond that, testing could have therapeutic impact. Patients who have defects in DNA-repair genes respond preferentially to PARP inhibitors and platinum-based chemotherapy.

These are patients with metastatic disease who don't have a good prognosis. You might buy time with next-generation anti-androgen therapy, but these patients invariably develop resistance and their tumors progress. Now there might be a therapeutic option with a PARP inhibitor or platinum-based therapy.

Explain what you mean by DNA-repair gene mutations. Why are these particular gene mutations important?

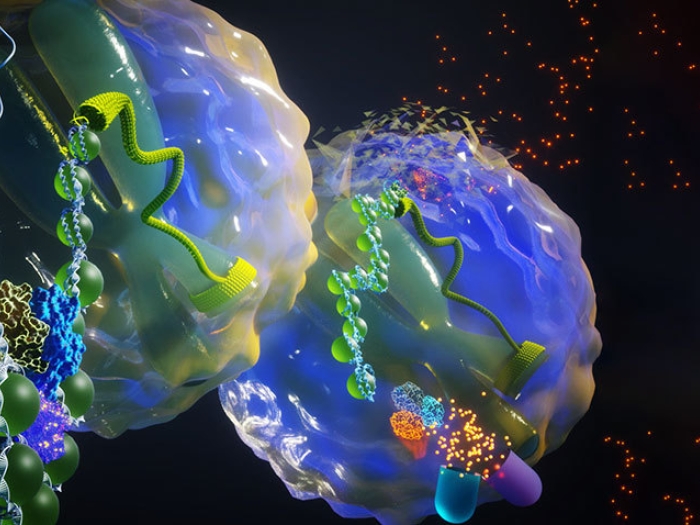

Chinnaiyan: The DNA repair pathway is a normal process of human cells to maintain the integrity of DNA. When cells replicate, they need to maintain their genetic code. If there's a defect in the DNA repair process, that leads to death of the cells. During normal cell division, you need to be able to maintain and repair your DNA effectively in order for cells to grow and for mutations not to accumulate.

In cancer, we can take advantage of the fact that a key component of the DNA-repair pathway is defective. That's essentially why PARP inhibitors work preferentially in cancer cells and not normal cells.

These findings suggest that where cancer occurs in the body is less important than what's driving it. How is our understanding of cancer shifting?

Chinnaiyan: There are a number of cancers in which DNA-repair alterations have been discovered. In fact, prostate cancer is not necessarily the best example. Typically we think of breast cancer and ovarian cancer where BRCA mutations play a role.

SEE ALSO: How Very Aggressive Cancer Cells Use Energy to Grow

The FDA has approved the PARP inhibitor olaparib for patients with BRCA-positive ovarian cancer. Subsequent studies have suggested PARP inhibitors could be effective in breast cancer patients with these defects. And now our work suggests prostate cancer patients should be considered for PARP inhibitors as well.

In fact, Maha Hussain, M.D., also of the University of Michigan, presented data recently at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting based on a clinical trial targeting a PARP inhibitor plus abiraterone in men with metastatic prostate cancer who had DNA-repair mutations.

Overall, this is another piece of data supporting the idea of precision medicine. We need to sequence patients' germline DNA, not only to predict their risk or their family's risk of cancer, but also to guide therapy in a more precise fashion based on the molecular blueprint of the patient's tumor. We know that PARP inhibitors don't have much effect in patients without DNA-repair mutations. This will allow physicians to better manage and treat patients.

You had many collaborators on this work. How has team science helped get us to this point?

Chinnaiyan: Team science is so important. Efforts like this take multidisciplinary teams. In this case, we had investigators from the University of Michigan, the University of Washington, Memorial Sloan Kettering, Weill Cornell, Dana Farber Cancer Center, Royal Marsden in the U.K. and others. These institutions each contributed patient samples to the analysis, allowing us to look at nearly 700 tumors. Our funding from Stand Up to Cancer and the Prostate Cancer Foundation pulled together teams who normally compete against one another. We need to work together to make studies like this happen.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!