Seen as the visual representation of the pandemic, one expert says the image should also be used as an educational tool.

12:20 PM

Author |

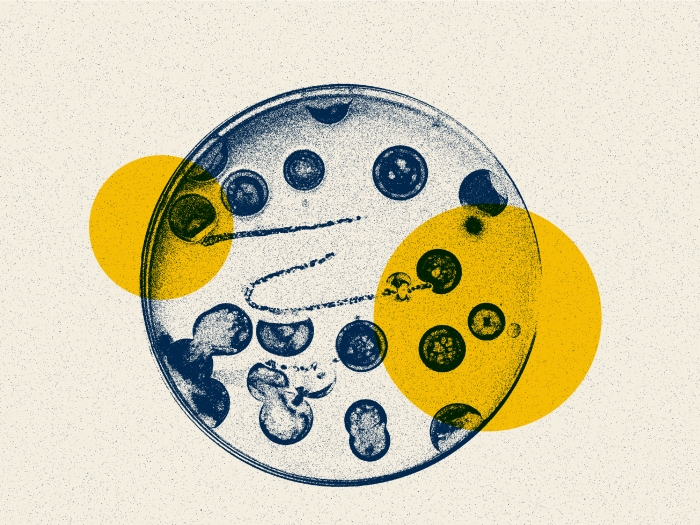

You've seen it—a large spherical mass with protruding red spikes plastered across the television and the internet. It's an image that has become all too familiar over the last few months.

We know it well as COVID-19, but what exactly does this picture tell us other than serving as the visual representation of the pandemic? Deb Gumucio, Ph.D., co-founder and director of U-M's BioArtography Project, which transforms stained research specimens into beautiful art pieces, has thought a lot about the impact scientific imagery has when understanding biological diseases, viruses and the human body in the time of the coronavirus.

"Right now, the image that everyone sees is essentially being treated like a brand," said Gumucio, also a professor emerita of cell and developmental biology at the U-M Medical School. "A lot of people look at this image and they don't have a lot of information about it—it looks a little like some sort of menacing alien machine."

The popular coronavirus image, created by medical artists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is actually a digital reproduction. While the images that Gumucio creates as part of her BioArtography process are from actual photo-micrographs, she says that the image we've seen circulating is a helpful visual tool.

SEE ALSO: Finding Beauty Through a Microscope

"It gives you a fairly accurate picture of the way the virus is put together," she says. "Those spikes on the outside are really there and they're what gave the virus its name—'corona' comes from the word crown in Latin, and those spikes bind to the receptor on a cell and allow the virus to enter it."

Like each image that BioArtography produces, the coronavirus' spiky ball tells a story, and that story has become an important visual cue about public health and safety.

"In the image, they added some orange and yellow-colored dots on the surface, which represent the myriad of proteins that the virus encodes," Gumucio said. "That's why washing your hands with soap is so important—it denatures those proteins on the surface. If the virus does not have those proteins, it cannot infect a cell."

She notes that the digital microscopic rendering of the virus is a good thing, and could actually serve as a constant public health reminder.

"Though the image doesn't often come with an explanation, people should know that it is a visual representation of how they have the power to destroy those proteins if they wash their hands thoroughly," she said.

According to Gumucio, the problem with the coronavirus image is that it is being treated as a brand for the virus, and not as the educational tool that it should be.

"I'd like to see more captions and more people talking about what the image can actually tell us," she said. "BioArtography promotes the idea that every single image that we generate is unique and tells a unique story about the image researched."

Gumucio wants us to think about the image in a different way the next time we see it.

"There is a lot of fear about the virus and the image that represents it," she said. "If people had more information to help them understand it, I think they'd feel a bit more confident that there are ways to defeat it."

Adapted from a story by Alana Valko

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!