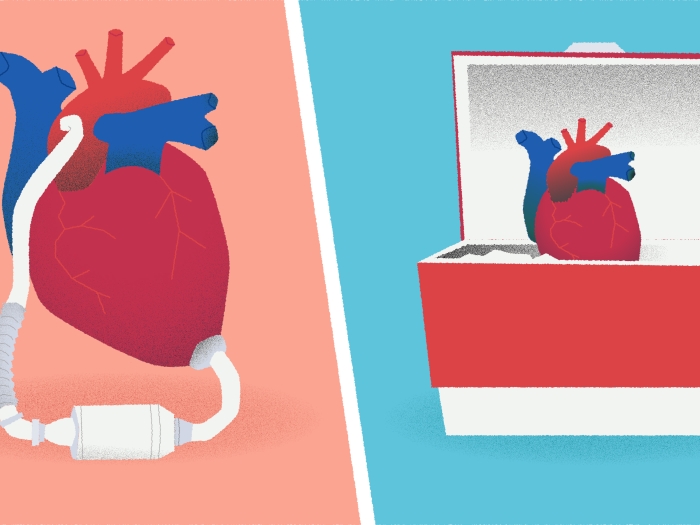

A new analysis of public data shows some hospitals are penalized for patients’ readmissions, though they do better at keeping patients alive.

7:00 AM

Author |

In the past few years, American hospitals have focused like hawks on how to keep patients from coming back within a few weeks of getting out.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Driven by new Medicare penalties for such events, the effort has slowed a revolving door of readmissions for heart attack, heart failure and pneumonia care that costs the nation billions of dollars.

But a new analysis suggests that Medicare should focus more on how well hospitals do at actually keeping such patients alive during the same few weeks.

If hospitals were paid less when patients died soon after a hospitalization, similar to readmission penalties, it would be a game-changer for one-third of hospitals, say researchers from the University of Michigan Medical School and Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System in JAMA Cardiology.

About 17 percent of hospitals are docked pay for excess readmissions, but are keeping patients alive in numbers higher than projected mortality rates.

Meanwhile, 16 percent of hospitals are essentially rewarded for low readmission rates. But their patients are more likely to die in the first month after leaving the hospital, after adjusting for factors like how sick patients were upon entering the hospital.

In other words, some of the hospitals most penalized for high readmissions may actually do a better job keeping patients alive — and vice versa.

Preventive action

If the penalties took both readmission and mortality into account, the Medicare system would save the same amount of money, but incentivize good outcomes more fairly, the researchers say.

"Under most circumstances, hospital patients would much rather avoid death than readmission," says Scott Hummel, M.D., M.S., senior author of the new paper and a heart failure cardiologist. "But the incentive to prevent death in the first 30 days after a hospitalization is 10 times less than the incentive to prevent a return hospital visit."

He and his colleagues, including first author Ahmad Abdul-Aziz, M.D., an internal medicine resident at U-M, and senior team members Rodney Hayward, M.D., and Keith Aaronson, M.D., M.S., hope their analysis will spark a conversation about how to fine-tune the Medicare system's effort to encourage better performance by America's hospitals.

The team analyzed publicly available data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), including some accessed through an online system Kaiser Health News created, from 2014.

That was the first year when hospitals could both be penalized for higher-than-expected readmission rates and earn a financial reward based on a mix of measures, including low 30-day death rates, patient ratings of care and the hospital environment. In all, data from 1,963 hospitals were included.

Under the current policy, hospitals can lose up to 3 percent of condition-related payments from Medicare for excess readmissions, but can recoup only about 0.2 percent of such payments for having low mortality rates.

The authors calculated a ratio for each hospital based on observed and expected readmissions and mortality in the first 30 days after heart attack, heart failure or pneumonia.

All the data were adjusted for how sick each hospital's patients were when they started, using standard methods that allow an apples-to-apples comparison. The socioeconomic status of each hospital's patients, which can also affect patient outcomes but isn't in a hospital's control, wasn't included because CMS hadn't yet started taking it into account in the year studied.

No one wants to see patients die because they should have been readmitted.Scott Hummel, M.D., M.S.

Balancing incentives

The authors don't take issue with the idea of penalizing excess readmissions — though they do note that readmissions for any cause are included in the program, not just readmissions for the problem that sent the person to the hospital in the first place.

SEE ALSO: Out-of-Pocket Health Care Costs: Why One Size Should Not Fit All

Admissions to any hospital within 30 days of discharge count against the hospital that initially discharged the patient, which may work against large hospitals that patients travel to for advanced care before returning to their home areas.

Other researchers have shown there isn't a close link between a hospital's 30-day readmission rate and the 30-day mortality rate for its patients with these conditions — suggesting that there's more to the story when thinking about using them as measures of hospital quality.

The authors also call for continued improvement in risk models that will more precisely predict a patient's risk of readmission, just like current, well-tested models to predict a patient's risk of death.

Better tools would mean better ability to test a hospital's actual performance against what might be expected based on its entire patient population. The researchers also plan to examine which kinds of hospitals are most likely to win or lose financially if the balance shifts between penalties for reducing readmissions and those for reducing early mortality.

"The misaligned incentives for preventing readmission and preventing death may help explain why some hospitals are doing really well on one but not on the other," says Hummel. "It's important that we continue to reduce preventable readmissions, but we need to watch out for unintended consequences, too.

"Sometimes, a readmission might be a good thing — no one wants to see patients die because they should have been readmitted," he adds. "If financial penalties drive hospitals to figure out how to improve outcomes, increasing incentives to reduce early post-hospital deaths seems like a good place to start."

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!