A novel strategy to target a genetic anomaly that occurs in half of all prostate cancers may provide a path for developing new therapies against it.

12:00 PM

Author |

It was truly a breakthrough in understanding how prostate cancer develops.

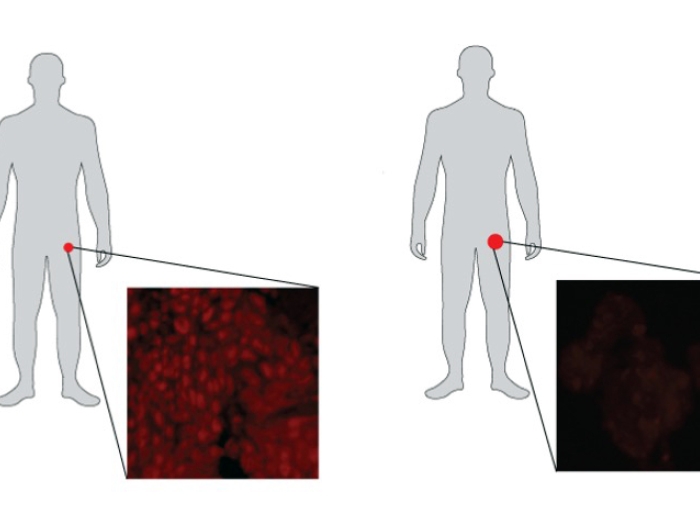

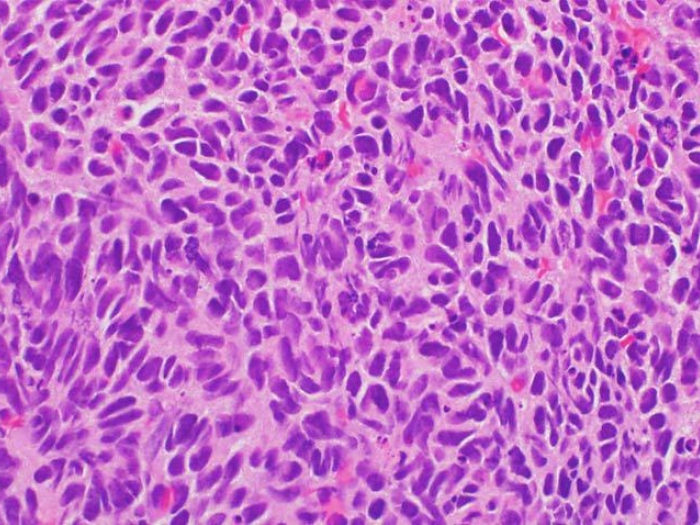

University of University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center scientists found that half of all prostate cancer tumors harbor a certain genetic anomaly in which the genes TMPRSS2 and ERG relocate on a chromosome and fuse together. This fusion was found to be an on-switch for prostate cancer development.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

The problem has been what to do with this knowledge. It turns out ERG is really challenging to target with the kind of small-molecule inhibitors that have had recent successes for treating cancer.

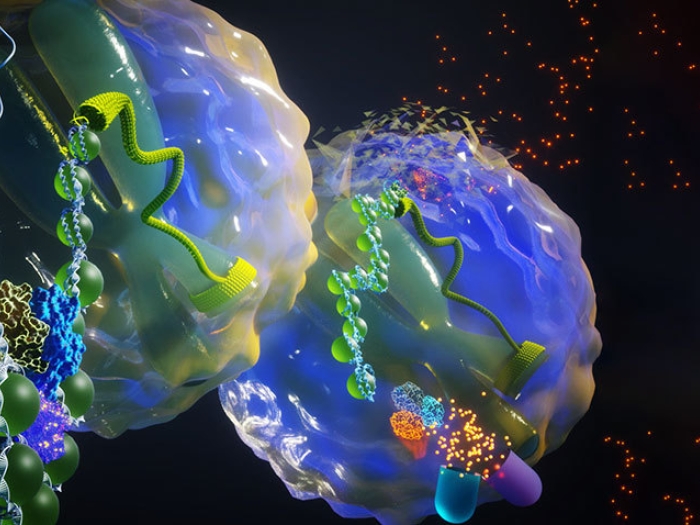

Now, researchers are reporting on a novel strategy to target the ERG gene fusion using large molecule peptides. Studies in cell lines and animal models suggest this approach can effectively target and degrade the ERG fusion with little impact on normal cell function. Their findings are published in Cancer Cell.

"Targeting this gene fusion product has been a major challenge. We had to approach this through a different angle," says senior study author Arul M. Chinnaiyan, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Michigan Center for Translational Pathology and S.P. Hicks Professor of Pathology at Michigan Medicine.

The researchers identified a panel of peptides that interacted specifically with the ERG protein. They tested the panel in cell lines harboring the gene fusion and found the peptides disrupted ERG function. In cells without the gene fusion, the peptides had little or no impact on gene expression.

They also looked at how the peptides impacted other biological processes regulated by ERG. These tests suggested that the peptides very specifically target the gene fusion without affecting normal cellular functions.

One problem was that peptides degraded quickly, not lasting long enough to travel to the desired target. So the researchers generated mirror images of the peptides. These peptidomimetics avoid the machinery that causes degradation of normal peptides in the body, leading to longer stability.

SEE ALSO: Quality of Life Meets Cure for Prostate Cancer Patients

Tests in animal models showed the peptidomimetics reduced the growth of prostate tumors that harbored the ERG fusion. After extended treatment, more than a third of the mouse tumors showed no signs of recurrence a month later.

"This is an example of how we can deliver precision therapy for prostate cancer: Only patients who have the ERG gene fusion would be matched with this agent. But it's useful because the ERG fusion is so prevalent," Chinnaiyan says.

One drawback to the peptide approach is that large molecules like this can't slip past the cell membrane. That means that the peptides need to be modified in some way or be delivered across the cell membrane. Small molecules are the preferred target for drug development because they can get inside of cells and bind to their target more easily.

Chinnaiyan's team will next work to create a three-dimensional outline of how the peptides bind to ERG in the hopes of turning this into a small molecule to inhibit ERG. In parallel, researchers will focus on making the peptidomimetics work better, with more potency in degrading the target.

Disclosure: The University of Michigan has filed a patent on peptidomimetic inhibitors of ERG described in this study, in which Chinnaiyan and Xiaoju Wang are named as inventors and the patent has been licensed by OncoFusion Therapeutics. Chinnaiyan and Shaomeng Wang are co-founders of OncoFusion, own stock and serve as consultants.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!