A genomic duplication may help explain why esophageal adenocarcinoma is much more common in Caucasians and presents a potential target for prevention.

7:00 AM

Author |

A change in the genome of Caucasians could explain much higher rates of the most common type of esophageal cancer in this population, a new study finds. It suggests a possible target for prevention strategies, which preliminary work suggests could involve flavonoids derived from cranberries.

Flavonoids are a class of water-soluble plant pigments that help protect against cancer, heart disease and other chronic health problems.

LISTEN UP: Add the new Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device, or subscribe to our daily audio updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

"We've known for a long time that esophageal adenocarcinoma primarily affects Caucasians and very rarely affects African-Americans," says David G. Beer, Ph.D., the John A. and Carla S. Klein professor of thoracic surgery and professor of radiation oncology at Michigan Medicine.

"We wanted to see if African-Americans have something genetic that's protective," Beer says. "If we understand why people have low risk, that can lead to understanding how to prevent cancer in those at high risk."

SEE ALSO: African-American Men More Likely to Develop Rarer Type of Esophageal Cancer

More than 17,000 Americans will be diagnosed with esophageal cancer this year. Adenocarcinoma represents about two-thirds of cases and is rarely seen in African-Americans.

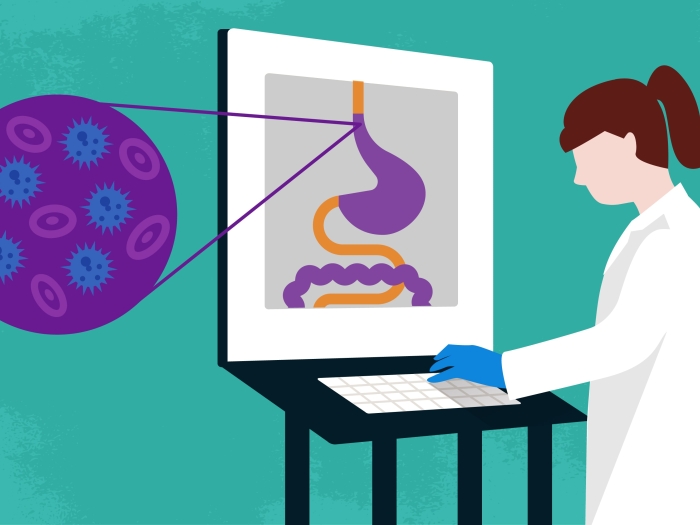

In the study, published in Gastroenterology, researchers examined tissue samples from African-Americans and European-Americans, including both those with esophageal adenocarcinoma and those without. They measured gene expression and protein levels and found a difference in the enzyme called GSTT2. This was significantly higher in African-Americans compared to Caucasians.

Researchers found Caucasians have a duplication on a portion of the genome that appears to reduce the expression of GSTT2. This enzyme protects cells against oxidative damage, such as the type caused by reflux, a key risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma.

They confirmed the initial findings by looking at expression and sequencing data from the 1000 Genomes Project, an international initiative that used genomic sequencing to provide a comprehensive view of human genetic variation. This data reinforced that populations from Africa or African descent had the non-duplicating genome, while all other populations around the world had the duplication.

MORE FROM MICHIGAN: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

"The risk factors for esophageal cancer such as obesity and reflux happen at the same rate for African-Americans and Caucasians. But African-Americans are not getting cancer," Beer says. "We see the highest risk of cancer in people who have this genomic duplication plus obesity. It's not just the presence of the duplication but these other factors contributing to the damage."

Rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma have increased 600 percent over the last three decades, caused by a rise in obesity and gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD. The other type of esophageal cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, is more frequently seen in African-Americans.

The researchers used cell lines and a rat model to re-create low levels of GSTT2. They saw more damage in these cells, compared to those expressing high levels of GSTT2.

SEE ALSO: Higher Rates of Esophageal Cancer Mortality Found in the Great Lakes, New England

Next, they used a cranberry proanthocyanidin extract and found it reduced levels of DNA damage in the esophagi of rats exposed to reflux. This suggests potential for preventing esophageal adenocarcinoma.

"The key with esophageal cancer is to prevent it. Many people don't know they have the disease until it's too late to treat it effectively," Beer says.

Researchers are considering a clinical trial to test using flavonoids derived from cranberries as a chemoprevention agent. However, more research is needed to understand appropriate dose and potential side effects.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!