No doctor in training should be penalized for addressing his or her mental health, one U-M student says. How she and her school are working to change attitudes.

1:00 PM

Author |

Rahael Gupta had good reason to take a hiatus from studying medicine.

The Oregon native, then 26, experienced depression so severe that the high-achieving pupil — who earned undergraduate and graduate degrees at Stanford and Columbia universities — almost took her own life.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

Withdrawn and fatigued, the woman who once ran marathons and kept an active social calendar one night considered stepping in front of an oncoming bus.

It wasn't the scenario a self-described "optimistic and fun-loving" person thought she'd ever encounter.

"Depression was like an opportunistic infection that took me over," says Gupta, whose issues began after failing a course in her second year at the University of Michigan Medical School. "I was sad, I lacked confidence, I was exhausted.

"And I tried to push through until it became obvious that simply wasn't possible."

A seven-month break to receive therapy and medication helped her feel stronger and more grounded.

After returning to school in 2017, though, Gupta soon realized that a choice rooted in self-care could have professional consequences.

"I spoke with a surgeon who is absolutely wonderful," Gupta recalls. "But he told me: 'As someone who values wellness I think what you're doing is great, but I have to be honest — if a student on their residency application said they were depressed, I would think twice about giving them an interview.'"

A recent U-M study found that many doctors are reluctant to report or treat their mental health issues — a byproduct of some states' rules that require physicians to report any mental diagnosis (no matter how mild or in the past) to medical licensing boards.

Several other faculty advised Gupta to vaguely cite health problems to explain her resume gap.

Although she knows their intentions were good, the 28-year-old chooses not to hide: "That's a vestige of stigma."

It's what compelled her to write and film a video featuring more than 30 U-M doctors, staff and students reading a first-person script based on Gupta's own experience with depression.

The effort, titled Physicians Connected, puts a public spotlight on her once-private emotions — ones that moved some participants to tears when reading the script aloud.

Gupta, who studied narrative medicine at Columbia, has also put her thoughts on paper by publishing a JAMA editorial this month about being depressed while in medical school.

"As an aspiring physician, I may be committing self-sabotage by telling my story," she writes in the essay. "I admit openly that I am just as vulnerable to the elements of life as are my future patients, hoping that others will do the same."

Both efforts buck façades of toughness or perfectionism that many students may feel compelled to display — and they offer hope, says Srijan Sen, M.D., Ph.D., a U-M associate professor of psychiatry and Frances and Kenneth Eisenberg Professor of Depression and Neurosciences.

"The level of struggle is at epidemic levels," says Sen, who has conducted extensive research on medical school and mental health, "but because of the culture of silence, people feel like they're the only ones going through it.

"This is an innovative way to break through that culture and help us talk about this critical topic."

Why depression affects medical trainees

Gupta is far from alone in her battles.

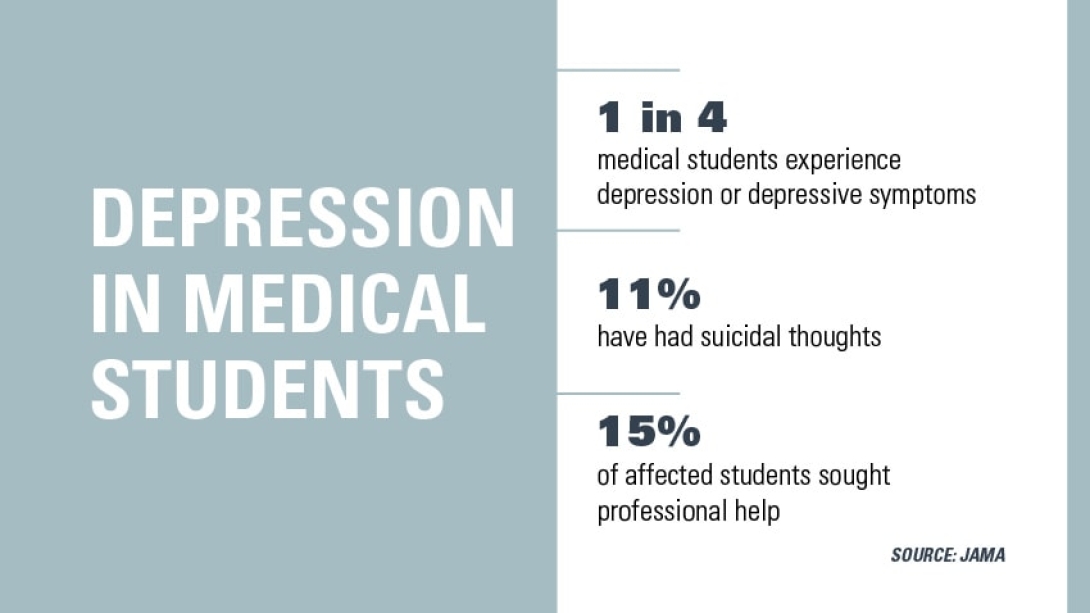

More than one-quarter of medical students experience depression, according to a compressive analysis reviewing nearly 200 studies that together surveyed 129,000 students. The analysis was published in JAMA in December 2016.

SEE ALSO: Study: Physicians Don't Report or Treat Their Own Mental Illness Due to Stigma

It's a rate of depression two to five times higher than the general population of the United States. Of the studies surveying whether participants had suicidal thoughts, 11 percent answered affirmatively (the overall suicide ideation rate for adults is 3.9 percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Perhaps most alarming, only 15.7 percent of affected medical students reported seeking medical help, the JAMA analysis found.

Sen, the report's co-author, has a personal connection to the cause: His friend and colleague committed suicide when the two were training physicians.

Medical students, Sen knows, face a brutal set of challenges: Rigorous academics, high-achieving peers and limited time to unwind can put even well-adjusted minds on shaky ground.

That risk has been shown to increase when these students begin their intern year, the first year of medical residency following graduation from medical school — a shift exacerbated by sleep deprivation, the pressure of caring for real patients, long hours spent managing electronic medical records and living alone in a new city.

Sen has deep insight on the subject. He has conducted the Intern Health Study since 2007. The longitudinal cohort study, which enrolls more than 3,000 new interns each year, offers a unique glimpse at a vulnerable population.

"It's a rare situation where we have an accomplished and well-adjusted group of people we know are going to encounter a major stress," says Sen, whose study has found that about a quarter of interns are depressed at any given point in internship — and that female interns are twice as likely to experience depression than males.

"But because of the culture of silence and brave face many of us present to the world, individual trainees often think that they are the only ones struggling and all of their colleagues are breezing through."

The data affirm his belief that academic institutions and teaching hospitals should offer students sufficient support throughout medical school.

Resources for medical trainees with depression

Most universities provide a variety of mental health services for the general student body, but few offer dedicated resources for medical students, residents and faculty, says Kate Baker, M.D.

Baker directs the House Officer Mental Health Program at Michigan's medical school. The program, established in 1996, allows residents to connect with several attending psychiatrists for needs such as depression, ADHD, anxiety and stress management.

A sister program launched two years prior for U-M medical students. For this and the house officer option, sessions may take place privately in the hospital or in an outpatient office.

"The treatment is completely confidential and doesn't appear on a trainee's academic record," says Baker, a clinical instructor in psychiatry. "We're available to do psychiatric evaluation and offer treatment — usually medication and psychotherapy if needed."

Gupta can attest to the power and necessity of those services: "It absolutely saved my life."

Many others have benefited, too. Last year, 140 U-M medical students and Michigan Medicine residents took advantage of the two programs, Baker says. Enrollment has increased slightly each year.

She and Sen are working to launch a telemedicine option so residents can receive counseling services remotely. Sen also has studied an online cognitive behavioral therapy tool known as MoodGYM and found that it may cut the rate of suicidal thoughts in half.

The level of struggle is at epidemic levels, but because of the culture of silence, people feel like they're the only ones going through it.Srijan Sen, M.D., Ph.D.

Improving access and accountability

Other efforts are in motion. Recently, the learning communities at U-M's medical school — a structure known as M-Home — doubled the number of medical school counselors from two to four. Each "house" now has its own dedicated mental health professional who functions as an academic/personal counselor to talk, provide crisis counseling and, if needed, offer referrals for ongoing treatment.

SEE ALSO: Advice for First-Year Medical Students: 5 Takeaways from Michigan M2s

The learning communities also sponsor wellness events such as meditation workshops, massage stations and therapy dog visits. House counselors are encouraged to attend in order to establish relationships and remind U-M medical students that mental health care is easy to access.

"We've become more effective and more intentional about weaving in these resources," says Tamara Gay, M.D., the medical school's assistant dean for student services.

And at an institutional level, the Michigan Medicine Civility and Wellness Taskforce was introduced in 2017 to encourage faculty, staff and students to take greater consideration of each other's emotions — and to foster more communication and courtesy across the system.

The scope of mental health initiatives represents a two-part strategy: address the issue and normalize the notion of self-care.

"First, we must provide robust support and services that are transparent, easy to access and effective for those who are struggling," says Rajesh S. Mangrulkar, M.D., associate dean for medical student education at the U-M Medical School.

"Second, we need to make connection, healthy activities, developing one's own meaning and purpose a part of medical school, not just something you do on the side."

Beyond treating the needs of medical trainees to ensure their well-being on campus, the open-door approach has big implications as graduates enter residency and the workforce.

"We know that doctors who are depressed commit medical errors twice as often," Sen says. "It so clearly impacts everyone."

Talking openly about mental health

Initially afraid to talk about her depression, Gupta was surprised by the response of her peers after she opened up: Many others felt the same way.

"The tears of my colleagues, the tales of deferred suicide attempts my classmates have confided in me and the tragic deaths of bright minds around the country lend strength to my conviction to proclaim my experience," Gupta writes in her JAMA essay.

SEE ALSO: Balancing Parenting, My Marriage and Medical School

Although she wants her video and written work to shed light on the value of initiatives such as counseling, fitness programs and promoting a work-life balance, Gupta wants a deeper dialogue to fuel wider systemic and cultural change.

She'd also like a greater sense of empathy from her professional peers.

A colleague who beats cancer is praised for bravery; a person successfully managing his or her depression might go unnoticed or, as Gupta's experience showed, be considered a liability.

"People in medicine love evidence and action items to address problems," Gupta says. "But no matter how hard you look at the human brain with a microscope you can't see depression."

Moreover, stigma can be eased by eliminating the verbal misnomers, joking or not, that accompany the pressure-cooker mentality of medical education.

Baker, who provides counseling services, knows the dialogue well: "At one point, I heard a trainee say 'If you're not feeling suicidal by six months into your intern year, you're abnormal' — which to me is just outrageous."

Baker often tells her clients to "give yourself permission to make life easier." That might mean signing up for a meal-delivery service, sending out their laundry, or ordering household basics via Amazon.

And Sen stresses the value of exercise and leisure activity when possible — directives that might seem like a tall order against the demands of medical education, but ones that pay off.

That's been a key part of Gupta's new routine. Expected to graduate in 2019, she integrates yoga and painting into her calendar. She also tends to succulents and herbs growing in a vertical garden in her apartment.

Writing, whether for herself or others, has helped bring her peace.

"It's a big part of how I make sense of my life," says Gupta. "My experience of being depressed doesn't make me incompetent. In fact, it makes me strong — and, more importantly, it makes me human."

Photo by Leisa Thompson

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!