An end-of-life care specialist reflects on how Medicare’s regulations for enrolling in hospice exclude many dementia patients who need it the most

9:15 AM

Written by Maria Silveira, M.D., M.P.H., FAAHPM, associate professor of geriatric and palliative care medicine

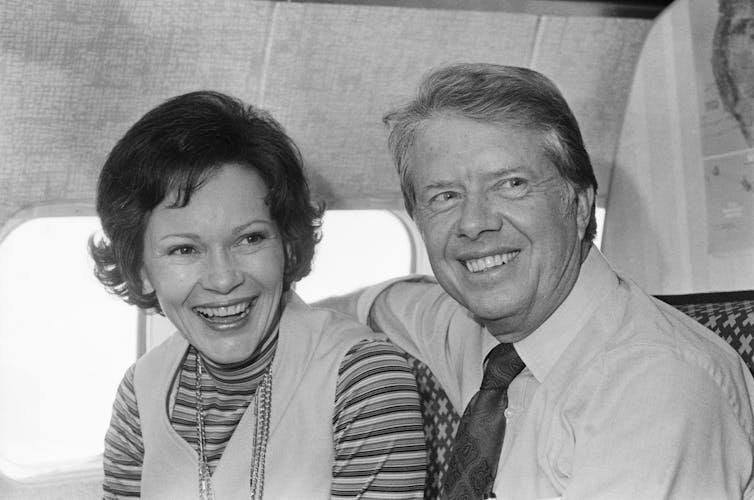

Jimmy Carter, who chose to forgo aggressive medical care for complications of cancer and frailty in February 2023, recently reached his one-year anniversary since enrolling in hospice care. During this time, he celebrated his 99th birthday, received tributes far and wide and stood by the side of his beloved wife, Rosalynn, who died in November 2023.

In contrast to the former president, his wife, who had dementia, lived only nine days under hospice care.

Palliative care physicians like myself who treat both conditions are not surprised at all by this disparity.

Hospice brings a multidisciplinary team of providers to wherever a patient lives, be it their own home or a nursing home, to maintain their physical and psychological comfort so that they can avoid the hospital as they approach the end of life.

Hospice is not the same as palliative care, which is a multidisciplinary team that sees seriously ill patients in a clinic or hospital to help them and their families with symptoms, distress and advance care planning.

Strikingly, only 12% of Americans with dementia ever enroll in hospice. Among those who do, one-third are near death. This is in stark contrast to the cancer population: Patients over 60 with cancer enroll in hospice 70% of the time.

In my experience caring for dementia patients, the underuse of hospice by dementia patients has more to do with how hospice is structured and paid for in the U.S. than it does patient preference or differences between cancer and dementia.

Rosalynn and Jimmy Carter campaign for the presidency in 1976. Bettmann via Getty Images

Rosalynn and Jimmy Carter campaign for the presidency in 1976. Bettmann via Getty Images

The role of Medicare

In the U.S., most hospice stays are paid for by Medicare, which dictates what hospices look like, who qualifies for hospice and what services hospices provide. Medicare’s rules and regulations make it hard for dementia patients to qualify for hospice when they and their families need support the most – long before death.

In Canada, where hospice is structured entirely differently, 39% of dementia patients receive hospice care in the last year of life.

The benefits of hospice

The first hospice opened in the U.S. in 1974.

Medicare began assessing the potential benefits of covering hospice care during Carter’s administration. The service gained popularity after Congress formalized a payment structure to reimburse hospice providers through Medicare in 1985.

At the time, lawmakers were responding to the realization that the cost of care at the end of life was the fastest-growing segment of Medicare’s budget. Most of those expenses covered costs for hospitalized patients with advanced incurable illnesses who died in the hospital after spending time in intensive care units.

Congress believed hospice would not only give seriously ill Americans an alternative to a medicalized death but would also help control costs. So it required hospices to provide holistic care to entice people to enroll in this new option.

The new Medicare coverage allowed hospice care to follow the patient wherever they lived, at home or in a nursing home. It would support families as well as patients.

These remain among hospices’ core values to this day.

A hospice nurse discusses how end-of-life care can become a life-affirming experience.

Impossible trade-off

In exchange, people enrolling in hospice would have to forgo other kinds of care, such as seeing specialists or being admitted to a hospital.

But letting go of specialists is a nonstarter for many patients.

Researchers have found that people with life-limiting illnesses like dementia are half as likely to enroll in hospice when they want to continue treatments they cannot receive in hospice.

Psychiatrists and geriatricians who treat dementia, and the psychologists, nurses, social workers and others who support them, are invaluable to families struggling to manage a dementia patient’s disruptive and sometimes violent behavior. They adjust and rotate medications such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, anti-epileptics or sedatives to help their loved one experience less anxiety, agitation or depression as their memory fades.

These adjustments are the norm for many patients with dementia who are particularly prone to side effects such as agitation or drowsiness. Specialized dementia teams are difficult to give up in exchange for hospice clinicians who are generalists following a protocol and adhering to a short list of approved medications.

But that is what Medicare currently asks these families to do.

The best of both

Hospice advocates and palliative care providers like myself believe dementia patients should have access to both specialists to provide expert guidance and hospice providers to support the care at home.

So-called concurrent care is the standard of care for children facing life-ending illness, as well as for patients in the Veterans Health Administration. There is evidence that the concurrent care approach helps patients and, ironically, saves money.

For around a decade, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has been studying alternative models for hospice that include concurrent care for Americans covered by Medicare. The agency is proposing to study the issue a bit longer. However, more studies will not bring relief any time soon to the 7 million Americans with dementia and their families.

Criteria for hospice

Even when dementia patients and their families are willing to forgo specialists and hospitalization, they are unlikely to meet Medicare’s stringent criteria for hospice, which were designed to limit hospice to patients who are expected to die within six months.

It’s so difficult to qualify for hospice under a dementia diagnosis that one of my colleagues is known for saying, “If you want to get a dementia patient into hospice, find a cancer.”

Medicare’s criteria require that people with dementia not only depend upon others for help with toileting, transferring, bathing, walking and personal hygiene but also that they be bedridden, incontinent, minimally verbal and have a terminal complication of dementia such as aspiration pneumonia, recurrent urinary tract infections, significant weight loss, or bed sores.

These complications typically occur only in the most advanced stages of dementia and are less likely when people receive quality care at home.

More importantly, Medicare’s hospice benefits do not provide patients with dementia and their families the support they need most – hands-on care.

Most people are shocked to hear that, aside from providing a bath aide a couple of times a week and a home health aide for brief periods to give a family caregiver a break, hospice does not provide the hands-on care that dementia patients – and, frankly, anyone who is in hospice – requires.

Monitoring, toileting, hand-feeding, repositioning, ambulating, medication administration and wound care are left up to family caregivers.

Families of people with dementia must either sacrifice their personal well-being and livelihoods to care for a loved one at home, hire a professional home health aide, which costs from US$30 to $50 an hour, or place the loved one in a nursing home. The latter is paid out of pocket unless patients qualify for Medicaid. And hospice care, as currently structured, does nothing to help with that.

My heart breaks for people like the patient with early dementia I met recently. His daughter-in-law – his sole caregiver – requested he be enrolled in home hospice, only to find out that not only did he not qualify for hospice, but that hospice would not provide the hands-on support they needed.

“So, unless we can afford to pay for an aide or place him in memory care, I’m all the hands-on help he’s got?,” she asked. “I’m afraid so,” I answered.

Given this impossible choice, it’s no surprise that Rosalynn Carter only entered hospice near the end of her life.

Maria J Silveira, Associate Professor of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine