Stress granules help the body’s cells protect their most important messenger, RNA — a process that could give clues to cancer and other diseases.

7:00 AM

Author |

A natural disaster. An unexpectedly bad financial report. The collapse of an industry giant.

All these events can send stock markets tumbling in minutes. Fortunes made over many years can vanish into thin air.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

But savvy stock traders can protect their clients' money by making rapid trades to invest in safe-bet stocks that won't lose too much value. Quick thinking and targeted trading can make a catastrophe much less damaging.

Now, research is showing that our cells may do almost the same thing. When stress strikes, our cells focus on socking away their most important free-floating material that relays genetic information — the kind that helps them grow and divide.

According to a team of University of Michigan researchers that have studied the phenomenon, the speed and accuracy of this activity may have a lot to do with the development of diseases as different as cancer and nerve-killing conditions such as Alzheimer's and Lou Gehrig's diseases.

Stress granules as safe harbors

Rather than storing away money in blue-chip stocks, our cells use something called a stress granule.

These tiny bundles of protein and genetic material have fascinated cell biologists for years. They show up as dark, dense areas in electron microscope images of cells that have been stressed by heat, chemicals or a buildup of imperfect cell products.

SEE ALSO: New CRISPR-Cas9 Tool Edits Both RNA and DNA Precisely

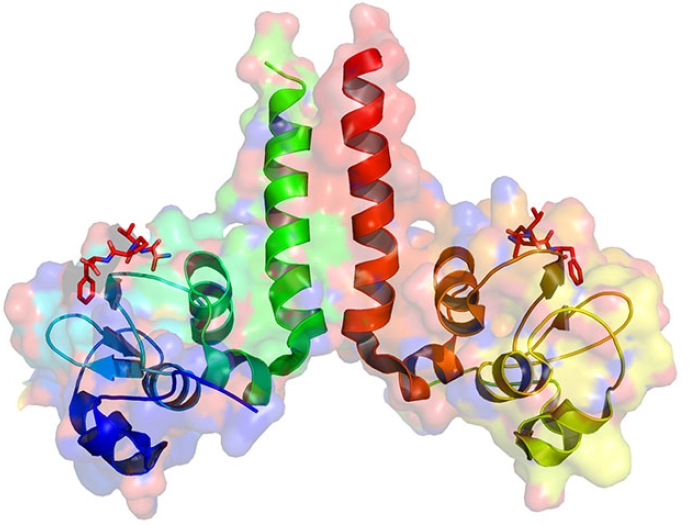

Researchers have probed the many proteins that can make up stress granules by carefully picking them apart in recent years.

But the genetic material inside them — in the form of messenger RNA, or mRNA — has resisted the same level of analysis. Each mRNA strand acts as the intermediate step between the instructions encoded in a gene and the protein that the cell can make from those instructions.

Generally, scientists have assumed that cells bind up whatever snippets of RNA happen to be floating in the cell's cytoplasm when stress strikes, snatching them indiscriminately to protect them from harm.

New research from the U-M Department of Molecular and Integrative Physiology, however, suggests that cells act much more strategically.

Preferential treatment

In a new paper in Molecular Cell, the team led by Jun Hee Lee, Ph.D., shows that cells focus on squirreling away the mRNA sequences that have the most to do with cell growth and proliferation.

The study gives the first side-by-side look of the impacts of different stresses on stress granule mRNA composition.

The reactions vary by circumstance. For instance, when the cell's own product-packaging machinery (the endoplasmic reticulum) gets bogged down with misfolded proteins, certain mRNAs get pulled into stress granules, the team finds.

Meanwhile, when a chemical- or heat-based stress is applied, cells might stash away other mRNAs.

It's as if the cells are putting the brakes on their own growth.Jun Hee Lee, Ph.D.

No matter what, the researchers found, stress granules generally bind up longer bits of mRNA, and ones that contain certain sequences called AREs (adenylate-uridylate-rich elements). Those AREs appear to play a key role in attracting the specific mRNAs that will be bundled into granules.

"We know that RNA complexed with protein is in there — and, in fact, that RNA is the major component of stress granules," says Lee, a professor of molecular and integrative physiology at U-M. "But only recently have we analyzed their function, how they localize to the stress granule and how that affects cell physiology."

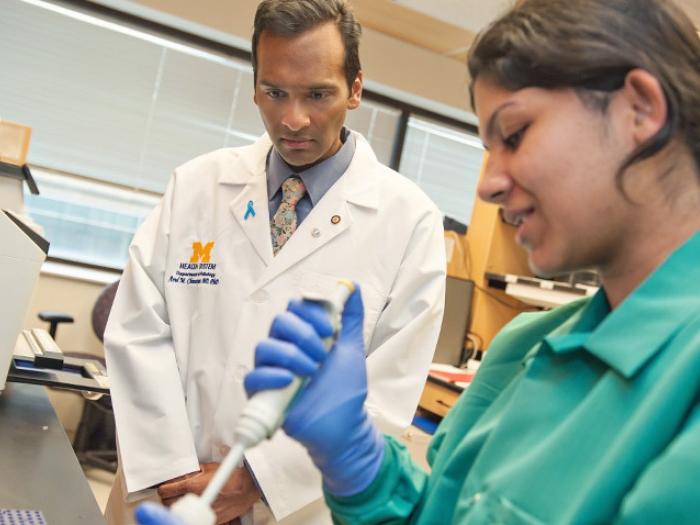

Lee and his colleagues, including first author Sim Namkoong, Ph.D., of U-M, and co-senior author Hojoong Kwak, Ph.D., of Cornell University, isolated all the messenger RNA in cells that they had subjected to stress and ones that they hadn't. The team used next-generation sequencing to spell out the mRNA sequences and figure out which genes they corresponded to.

"Not all RNAs get sequestered, and ones that are essential for cell survival and growth were preferentially sequestered into granules," says Lee. "It's as if the cells are putting the brakes on their own growth."

Protecting valuable assets

One of the key types of mRNA that Lee and his colleagues found in stress granules was the type generated by proto-oncogenes. In their normal form, such genes are crucial to regular cell growth. But a mutation in them can lead to out-of-control growth and development — in other words, cancer.

SEE ALSO: How Very Aggressive Cancer Cells Use Energy to Grow

The fact that proto-oncogene products were preferentially sequestered into stress granules indicates their importance, but also reinforces previous findings that stress granule dysregulation is closely linked to cancer.

Lee and his team are now working on further studies of how the granulation process is misregulated in cancer.

They're also looking at the mix of mRNA found in stress granules in nerve cells — the kind of cells that die out in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also called Lou Gehrig's disease) and Alzheimer's disease. Other research has shown that stress granules accumulate in such cells, and hinted that the granules themselves may be defective.

Still, there is much more to learn.

"Stress granule formation can be a universal mechanism for cells to deal with stresses of all kinds, but we still don't understand how cells form these granules, nor what happens to the mRNA inside them once the stress eases and conditions become more favorable," says Lee. "Perhaps the proteins involved in granulation are also involved in unwinding the mRNA and allowing it to continue toward its intended use to drive protein production."

Just as most stockbrokers go back to normal trading after the adverse financial conditions have eased, Lee suspects that cells may become less conservative in their mRNA traffic after stress has passed.

And whether it's money or living cells at stake, the goal is the same: preserve precious assets, and grow them.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!