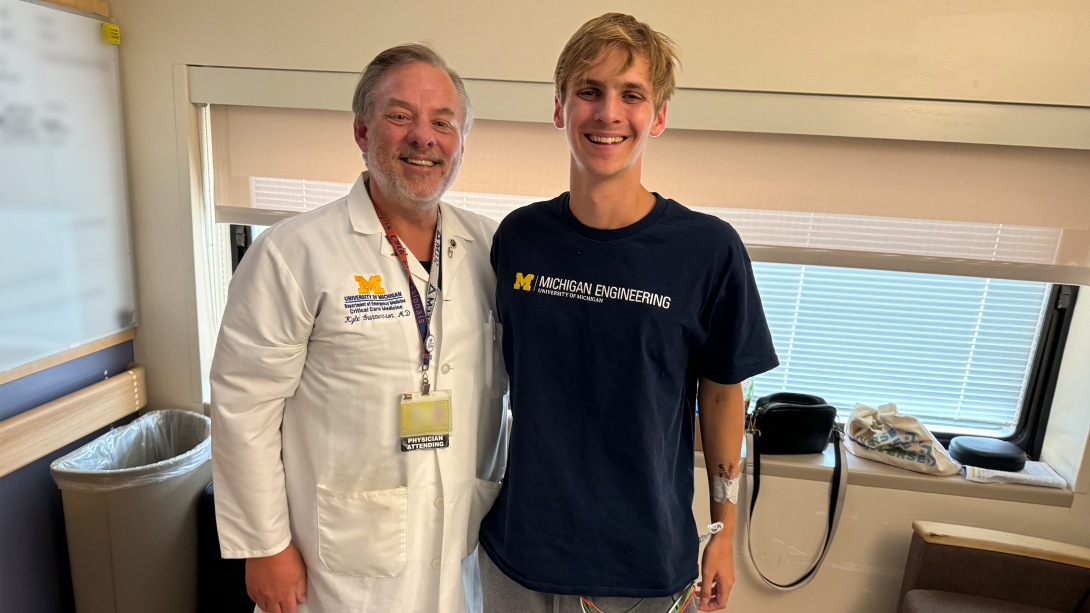

Ethan King, 18, was back in class less than two weeks after the incident

10:02 AM

Author |

After collapsing on a run during his first week of college, a University of Michigan student is advocating for increased awareness of sudden cardiac arrest and the importance of learning CPR.

“I never would have expected that this could happen to me,” said Ethan King, 18, a first year from Fairfax County, Va.

“I’m a healthy guy. I have run almost every day for years and don’t eat much junk food. The randomness of it was like a lightning strike.”

One day before his heart stopped, the former high school athlete — who had qualified the previous year for the state championship in Virginia — attended a U-M club fair. He joined the running club and signed up for a seven-mile afternoon jog on Thursday, August 29.

The club split off into groups. Around a mile into the run, King stumbled on a curb in Ann Arbor’s Burns Park neighborhood.

“For a minute he was conscious, but he couldn’t get any words out,” said Nolan Tribu, 20, a junior and social chair of the campus run club.

“A few of us ran over to try and help. He wasn’t breathing.”

The chain of survival

Someone called 911, but no one in the club knew how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR.

Hannah Stovall, 21, pulled over. The senior, who had just finished playing pickleball with a friend, had been certified in CPR for six years.

Stovall started chest compressions, commonly called hands-only CPR. Tribu followed with rescue breaths.

Before any EMS providers arrived, another driver stopped to help: Derek Dimcheff, M.D., an off-duty hospitalist at University of Michigan Health and the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

“I respond to codes in my duties as a physician. Not seeing any EMS, I felt I should stop,” said Dimcheff, who was driving to pick up his son, a sophomore at U-M.

“I was, however, quite impressed that bystanders were attempting CPR because early action is critical. The team effort helped save his life.”

SEE ALSO: Her heart stopped more than 25 times. ECMO saved her life

Dimcheff continued on a blue-faced King until EMS arrived and hooked him up to an AED.

After a couple shocks, they loaded him into the ambulance.

Ethan King was breathing, and his heart was sustaining its rhythm — what’s known medically as a return of spontaneous circulation.

“I was afraid because CPR has such a low success rate, so I was very glad when I overheard the paramedics say he had a pulse,” Stovall said.

Surviving cardiac arrest

Most cardiac arrests in the United States occur outside of the hospital, but fewer than 10% of people survive.

At University of Michigan Health’s emergency department, King’s care team focused on ensuring that the 18-year-old would retain as much of his brain function as possible.

“The CT scan of his brain looked fine, so we began cooling his body down to 32 degrees Celsius for 24 hours in an effort to reduce any potential brain injury that could occur after blood flow is restored,” said Kyle Gunnerson, M.D., FCCM, an emergency physician at U-M Health.

“While research is still ongoing, patients who undergo cooling shortly after having return of spontaneous circulation, and are prevented from developing a fever, have seen improved neurologic recovery. We wanted to ensure that Ethan had every chance to fully recover to where he was before his cardiac arrest."

In Virginia, Ethan’s mother, Carrie King, received a call from a social worker at the hospital.

We have your son here, she recalls hearing.

“I assumed he broke a bone while he was out running or something,” Carrie King said.

“We had just dropped him off, and he told us how much he was enjoying it. Never in a million years did I think they would tell me he was in a coma.”

The King family got in the car and drove 530 miles to Ann Arbor. They got to the hospital early Friday morning.

“Dr. Gunnerson was very positive on our call, but I was concerned about Ethan having brain death,” Carrie King said.

“We wouldn’t know his brain function until he woke up. It was something I didn’t want to say in front of my daughter. We almost had her stay home, but we wanted to bring her in case we had to make a hard decision.”

One day later, Ethan squeezed his mother’s hand. The care team woke him up and removed his breathing tube on Sunday, September 1.

“We were crying tears of joy and excitement,” Carrie King said.

“Ethan was out of it, but he was talking — he even remembered his dog’s name. Whatever it was going to be, he was alive and able to interact. We knew it could only go up from there.”

I was, however, quite impressed that bystanders were attempting CPR because early action is critical. The team effort helped save his life.”

-Derek Dimcheff, M.D.

Ethan King did not remember the cardiac arrest or anything from that day. More than one month later, he says, it still doesn’t feel like it happened to him.

“Because I don’t remember a lot, it just doesn’t feel real,” he said.

“I felt weak, but it didn’t really sink in until I went in for surgery.”

To prevent his heart from stopping again, doctors placed a subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator, or S-ICD, under Ethan’s skin.

The device, implanted by electrophysiologist Jackson Liang, D.O., at the U-M Health Frankel Cardiovascular Center, is designed to shock the chest if a patient’s heartbeat becomes abnormal.

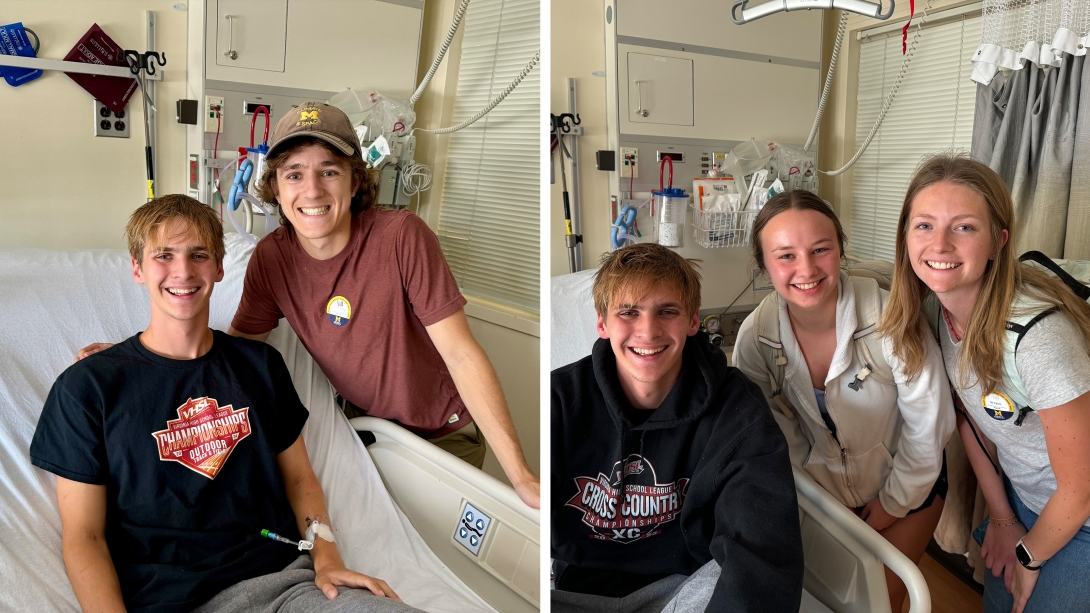

As he recovered in the hospital, Ethan’s classmates, including Hannah Stovall and Nolan Tribu, visited.

“After the incident, I didn’t know anyone connected to Ethan,” Stovall said.

“It was a hard few days, but I was finally able to take a breath once I saw him in the hospital. It was so great seeing him doing well.”

Dimcheff, who was not involved in Ethan King’s care after performing CPR, also stopped by.

“I worried about him a lot before I knew he’d done well. I have two sons who are of a similar age and really felt for the family,” he said.

“I have responded to cardiac arrests outside of the hospital in the past, and not everyone has had a result like this. I cannot emphasize enough how great it was that people started working on him so quickly.”

SEE ALSO: Heart attack at Michigan-Ohio State game ends in win for Ohio photographer

While the memory may not exist, Ethan says, he will never forget Stovall, Tribu, Dimcheff and all the other bystanders who acted after he collapsed.

“It’s hard to sum up the gratitude in words,” he said.

“It’s not something many people can say literally: They saved my life. There is really no way to ever repay that.”

Doctors conducted several tests to determine what may have caused Ethan King’s heart to stop. He was released on September 7, and his providers are still looking for an answer.

CPR awareness

The Kings decided not to pull Ethan out of school after leaving the hospital. He has to fit doctor’s appointments between classes and activities, but his parents did not want him to miss his college experience.

“Being an occupational therapist, I know that taking someone out of their routine can do more harm than good sometimes,” Carrie King said.

Once physically ready, Ethan King plans to return to sport and rejoin the running club. Though he’s told the story dozens of times, he says he does not want the focus on him as “the boy who lived”.

Instead, he wants to talk about why all of his classmates should know CPR and how to spot cardiac arrest.

Each year, around 2,000 people under the age of 25 die of sudden cardiac arrest in the U.S. The signs someone is experiencing cardiac arrest include chest pain, shortness of breath, being nonresponsive and loss of consciousness.

Not only did Nolan Tribu get CPR-certified in the month after the incident, but he and Stovall helped put on hands-only CPR training events for the running club in early October.

“You could not have asked for a better reaction from bystanders during Ethan’s cardiac arrest,” Gunnerson said.

“When a young athlete goes down, the first instinct is not to think it’s a cardiac arrest. But having the skills can help you feel less afraid to act if it does happen. Anyone can save a life by knowing basic CPR.”

Special thanks to first responders Callie and Tim from Huron Valley Ambulance, and to all others involved with the incident response.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Clinical Professor

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!