An international study identifies inherited factors that may increase a child’s risk for developing nephrotic syndrome — and could also help target better care.

7:00 AM

Author |

Researchers have found new genetic clues linked to an increased risk of children developing nephrotic syndrome.

LISTEN UP: Add the new Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device, or subscribe to our daily audio updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

An international research team, which includes University of Michigan C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, studied the genomes of nearly 400 children with the debilitating kidney disease in France, Italy and Spain. Another 100 children in North America enrolled in the Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (NEPTUNE) were also studied.

Across both continents and patient groups, the findings were the same: Researchers discovered genetic variants from three regions of the genome associated with pediatric nephrotic syndrome.

The condition prevents kidneys from filtrating blood properly, leading to massive amounts of protein loss in the urine, including important clotting factors and antibodies to fight infection. Although nephrotic syndrome occurs in only 2 to 7 of every 100,000 children each year, it is the most common childhood disorder of the kidney's filtration unit, the glomerulus.

U-M led analysis also reveals that two of the identified genetic variants are associated with a significantly increased likelihood of experiencing complete remission. If this discovery is supported in future studies, it could suggest that children with nephrotic syndrome and these variants are more likely to have better outcomes.

The findings appear in this month's Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

"The more precisely we can understand the molecular mechanisms of nephrotic syndrome, the better we can develop targeted and effective care for our patients," says Mott pediatric nephrologist Matthew Sampson, M.D., one of study's senior authors and head of the kidney-focused Sampson Lab at U-M.

Evolving those care methods, Sampson notes, is critical.

"Currently, we use steroids and other treatments to try to prevent the disease from progressing to chronic kidney disease and end-stage kidney disease, but these medications are nonspecific and come with significant side effects."

Continuation of kidney disease research

The research was a collaboration among U-M, Sorbonne University and Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, in France, and the Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù, in Rome, Italy.

Across countries and continents, children with nephrotic syndrome who harbored the identified risk variants were significantly younger at the age the disease started compared to young people that didn't.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

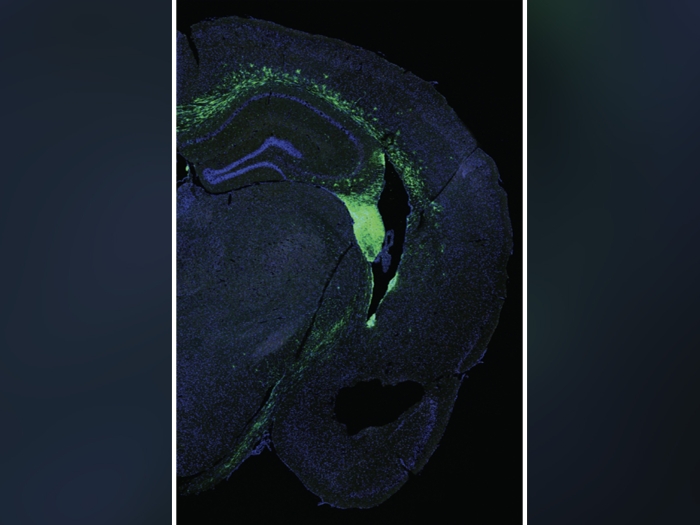

Two of these genetic variants were also associated with decreased kidney expression of specific human leukocyte antigen genes (which code for proteins and are responsible for regulating the immune system) within the kidney's filtration barrier in patients with the condition.

All risk variants are also associated with other immune-mediated diseases, which authors say strongly supports that this form of nephrotic syndrome is yet another human condition characterized by immune dysregulation. Sampson notes it is now necessary to figure out the unique combination of genetic and environmental factors that combine to result in a child getting nephrotic syndrome specifically.

"Collaborating with international colleagues on this work allows us to study larger sample sizes across the globe, which is critical to better understanding the genetic underpinnings of this rare but debilitating disease," Sampson says.

"Further research including larger populations of pediatric patients with nephrotic syndrome will help us identify more characteristics that increase children's risk to developing this disease and make more discoveries that will help us fight it."

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!