Renowned neuroanatomist Elizabeth Crosby was a brilliant researcher and a dedicated teacher whose students adored her. She spoke of her many years at U-M with fondness. So why did she try to resign numerous times over the course of her career?

Author |

On October 15, 1937, the chair of U-M's Department of Anatomy, Bradly Patten, received a letter of resignation that spurred him into action. It was from Elizabeth Crosby, Ph.D., a star in the field of neuroanatomy, and she was leaving U-M.

Patten immediately wrote to the dean of the Medical School, Albert Carl Furstenberg, asking for help in persuading her to stay.

Furstenberg quickly wrote to Crosby, reminding her that she had the "profound admiration and respect of the President of the university, myself, the Director of your Department, and every member of the Medical Faculty, as well as the student body."

Though Crosby ended up staying, she would attempt to resign four times over the course of her career. It's an odd pattern for a researcher and professor who was so highly regarded, and who said of U-M, "I only feel gratitude for my time at U-M."

A Beautiful Mind

Elizabeth Crosby was born in 1888 in Petersburg, Michigan. She was so frail at birth that she almost died, and so sickly that her parents would sometimes "put her in the oven for short spells to bring the color back into her cheeks."

After graduating from Adrian College in 1910, Crosby attended the University of Chicago, where she earned her Ph.D. in neuroanatomy in 1915, with a thesis that remains important today.

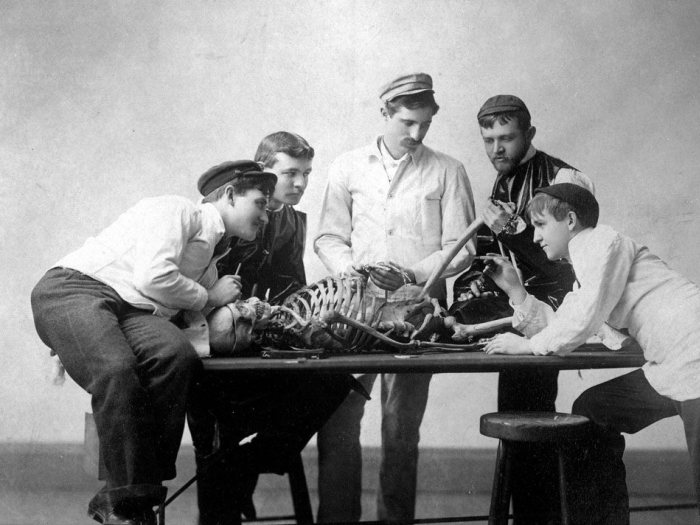

In 1918, Crosby became a junior instructor at U-M under Carl Huber, a professor of anatomy.

Huber and Crosby became close and effective collaborators. Together, Crosby and Huber produced the 1,800-page work The Comparative Anatomy of the Nervous System of Vertebrates, Including Man. It was comprehensive, accurate, and so detailed that its authority was accepted almost immediately.

Tragically, before it could be published, Huber died in the fall of 1934. "No one will ever be able to assess the shock and sense of loss which this event caused Doctor Crosby," wrote Russell T. Woodburne, a U-M professor of anatomy, in a short biographical sketch of Crosby.

It also left Crosby's role in the department in limbo.

"A Source of Embarrassment"

Crosby wrote her first resignation letter to Dean Furstenberg on February 21, 1935. She began by citing her gratitude for her promotions from junior instructor to associate professor.

The problem, however, was with her gender.

"It would seem that a woman in my position, as second ranking member in the Anatomy Department, might, under all the circumstances, prove a source of embarrassment to you as Dean and to the Executive Faculty of the Medical School. This has been apparent to me since Dr. Huber's death."

She proposed to Furstenberg that she be demoted and returned to a quizmaster and laboratory assistant until she could find another position — unless Furstenberg could find any "middle course" in the situation.

Friends counseled Crosby to not do anything rash, and she ended up staying.

Patten's Folly

In early 1936, Bradley Patten became the new chair of the Department of Anatomy, replacing Huber. He quickly recommended Crosby for the position of full professor.

"Dr. Crosby is one of those unassuming persons whose brilliant work has been done so quietly that one finds her almost better known abroad than within her own University."

Crosby accepted, becoming the first woman to hold a full professorship in the Medical School.

But her October 1937 resignation letter (cited at the start of this story) wasn't far off.

Crosby's would-be biographer, neurosurgeon Richard Schneider, may have uncovered clues that her working conditions at the time were far from ideal.

In the course of his research, Schneider received a letter from John Bean, M.D., who was chair of the Department of Physiology. He told Schneider that Crosby and Patten's relationship was strained. In one instance, Patten forced Crosby to build and use an enormous life-size model of the entire human nervous system for her classes, with wires for nerves. The Anatomy Department called it "Patten's folly."

Patten also dismantled a special research library Crosby had developed with Huber, according to Bean. Patten even insisted Crosby retire before him so that "any honors which might be due [Patten] would not be dismantled by her greater reputation."

"Despite her statements . . . that she never was discriminated against, it seems to me that this was [a] real cover up, for she had a major degree of discrimination in actuality," wrote Schneider.

Persevering

Crosby acknowledged that women in her field had experienced discrimination, but never counted herself among them.

Crosby's attitude, writes Leslie Lin in the Research News, "seems typical of her generation's female scientists. They asked for so little that any recognition they did achieve was regarded as a 'bonus' rather than their due."

Still, after her 1937 resignation attempt, Crosby would almost leave twice more — considering offers from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland and Marquette University in Wisconsin.

U-M won out in the end, and Crosby worked for the University for decades, even after her retirement in 1959.

Ten women wrote their doctoral dissertations under Crosby, and she taught more than 8,500 students.

Before her death, she was honored by every major professional organization in her field. In 1980, she received the National Medal of Science from President Jimmy Carter.

Sources for this story include:

The Elizabeth Crosby Papers. Lin, Leslie: The Research News, University of Michigan, August-September 1933. Whitehouse, Bradley: "The Quiet Genius," Adrian College Contact, Winter 2005.

This article was originally published in Collections, the U-M Bentley Historical Library Magazine.