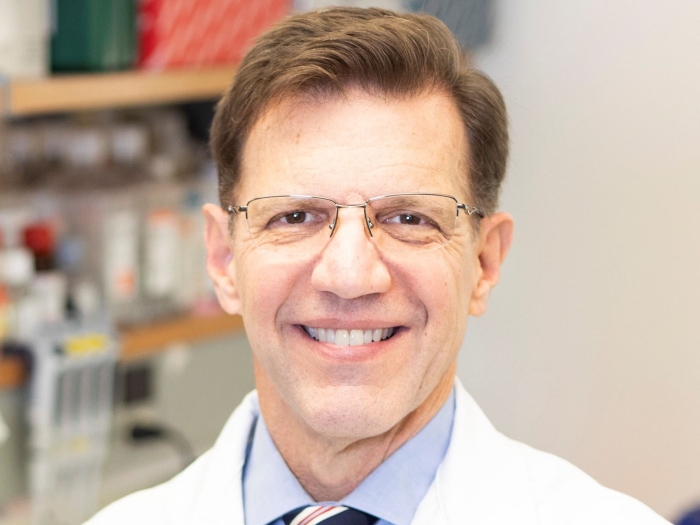

Marschall Runge, in his new role as dean of the Medical School, is implementing his vision to ensure U-M continues to provide the very best, value-based medical care for our patients

Author |

Marschall Runge, M.D., Ph.D., spent his first six months at the University of Michigan running the administrative equivalent of lab tests and EKGs: looking, listening and learning. He knew changes were coming — they are always coming in the American health care system — but he wanted to understand U-M before he made major changes.

"I was not surprised to confirm that Michigan combines a great medical school with a great medical center, demonstrating excellence in teaching, research and patient care," Runge says. "I was also happy to find, and this is rare, a culture of respect. At the end of the day, everyone wants to provide the best care for the patients we serve. Our scientists are committed to discovery and innovation, and they respect our clinical leaders. And our clinical leaders believe our research will help us deliver better patient care."

As of Jan. 1, Runge's role has officially expanded. He began as the executive vice president for medical affairs and CEO of the U-M Health System. Now, he is also dean of the Medical School. This is the latest step in a medical career that has its roots in a family nearly full of physicians.

Homegrown Medicine

By the time Runge arrived in Ann Arbor, he had studied in Nashville and Baltimore, and worked in North Carolina and Texas, among other places. But he was always surrounded by medicine. His grandfather was a physician, as were his father and mother. His brother and sister are as well, and so are his wife and several of their five children.

A Texas native whose manner mixes to-the-point seriousness with wry humor, Runge graduated with a Ph.D. from Vanderbilt University and earned his M.D. at Johns Hopkins University. He also taught and held high-level administrative posts at Emory University, the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston and the University of North Carolina, where he was executive dean of the medical school and the principal investigator for its translational medicine research institute. He holds five patents, including one for a recently FDA-approved treatment for hemophilia, and serves on the Eli Lilly and Company board of directors.

"What you know about Marschall [in the examining room] is that he cares," says Andrew Greganti, M.D., who was both a patient of Runge's and a colleague at UNC. "He listens to your particular needs and really tries to modulate his responses to take into account what you are comfortable with. He makes the patient feel informed about what's going on."

Runge moved his lab — which is investigating how reducing oxidative stress can prevent atherosclerosis and associated cardiovascular disease — from North Carolina to Michigan, and he will also be clinically active, beginning with attending on the cardiology consult service.

Susan Runge, M.D., Runge's wife of 35 years, says it's an innate interest in helping that inexorably pulled him to leadership roles. "I don't think he ever aspired to move up the chain of command," she says.

When they met at Vanderbilt — where he was the "smart, optimistic, jovial and handsome" captain of the tennis team — he was intent on becoming a researcher. But through the years he was offered and then pursued more administrative opportunities that tapped "his ability to listen to people, hear out problems and complaints," Susan says.

According to Susan, and others who know him well, these same qualities guide Runge's personal life.

"He doesn't have a broad range of interests," she explains. "Instead he focuses on, and excels at, a few areas: medicine, family and tennis."

Myron L. Weisfeldt, M.D., who has known Runge since his days at Johns Hopkins in the early 1980s, says Runge always remains focused on results. "His approach is simple: Let's deal with the real issues and get the job done."

At work, one of Runge's most apparent qualities is his ability to "take pride in other people's success," says Don W. Powell, who recruited Runge to Galveston. "It helps that he genuinely enjoys working with others and has an intimate knowledge of the challenges they face because he has been in their shoes."

New Decisions

Runge has made a series of decisions to begin implementing his vision at Michigan. These include helping complete long-discussed projects to expand and improve patient care. In July, he and the Health System gained approval from the U-M Board of Regents to build a new $46 million, 75,000-square-foot medical facility that will expand primary and specialty care, as well as other health services, in Ann Arbor.

In November, the Health System announced plans to build a new 320,000-square-foot health center to provide expanded primary and specialty care in the Brighton area.

Runge also announced a $150 million commitment over the next five years to bolster biomedical and translational research. He wants to help clinicians and researchers collaborate across disciplines — including computer science, statistics and social science.

It's all a part of the simple mission that has guided him through his life and work: help those around him live happier, healthier lives.

"My goal," Runge says, "is to ensure Michigan's position as one of a handful of top institutions pursuing bioscience research and education in the United States and the world — as judged by the quality and number of transformative discoveries in the field, the success and impact of our students and trainees, and the quality of care we provide."

As at other academic medical centers, clinical care is Michigan's main revenue generator and supports the research and education wings of the mission. The clinical programs, in turn, depend on researchers to advance care and on the Medical School to educate tomorrow's clinicians. As he has said many times, "The drive behind our research and educational programs is to provide the very best, value-based medical care for our patients, whether it is in disease prevention or expertise in the most complicated and intricate of therapies."

In a fast-changing landscape defined by intense pressure to control costs and increase value, Runge believes the institution must create a common spirit among these three divisions so that decisions are made with an eye toward the efficiency, effectiveness and vitality of the entire operation. He is working toward another goal: changing the nature of decision-making so that it's not only a series of choices on discrete projects, but a reflection of the broader mindset and overarching strategy essential to Michigan's future success.

During his career, Runge has seen, too, that collaboration can be a double-edged sword. "The ethos of consensus is important and powerful, but it has also hindered the decision-making process," Runge says. "When you delay or refuse to make a decision, you're deciding not to act. I want to encourage a culture of calculated risk-taking, where we're not afraid to make mistakes."

He adds: "Don't let perfect be the enemy of the good."

Michigan's New Leaders

Last year, U-M President Mark Schlissel recommended that Runge become the first individual to head the U-M Health System and the Medical School. Runge is in a position to direct resources where they are most impactful across the organization. Runge, in turn, is assembling a management team to focus on specific areas within the context of the big picture. He has already appointed David Spahlinger, M.D., as executive vice dean for clinical affairs with oversight of the hospitals, outpatient care and medical centers. Searches are ongoing for the executive vice dean of academic affairs, who will help Runge run the Medical School with additional focus on improvement, branding and marketing. The chief scientific officer will guide the research enterprise, helping U-M become one of the top five recipients of NIH grants — in 2015, it ranked 10th. NIH grants are a marker, a means to an end of making U-M home to high-impact discoveries and innovations.